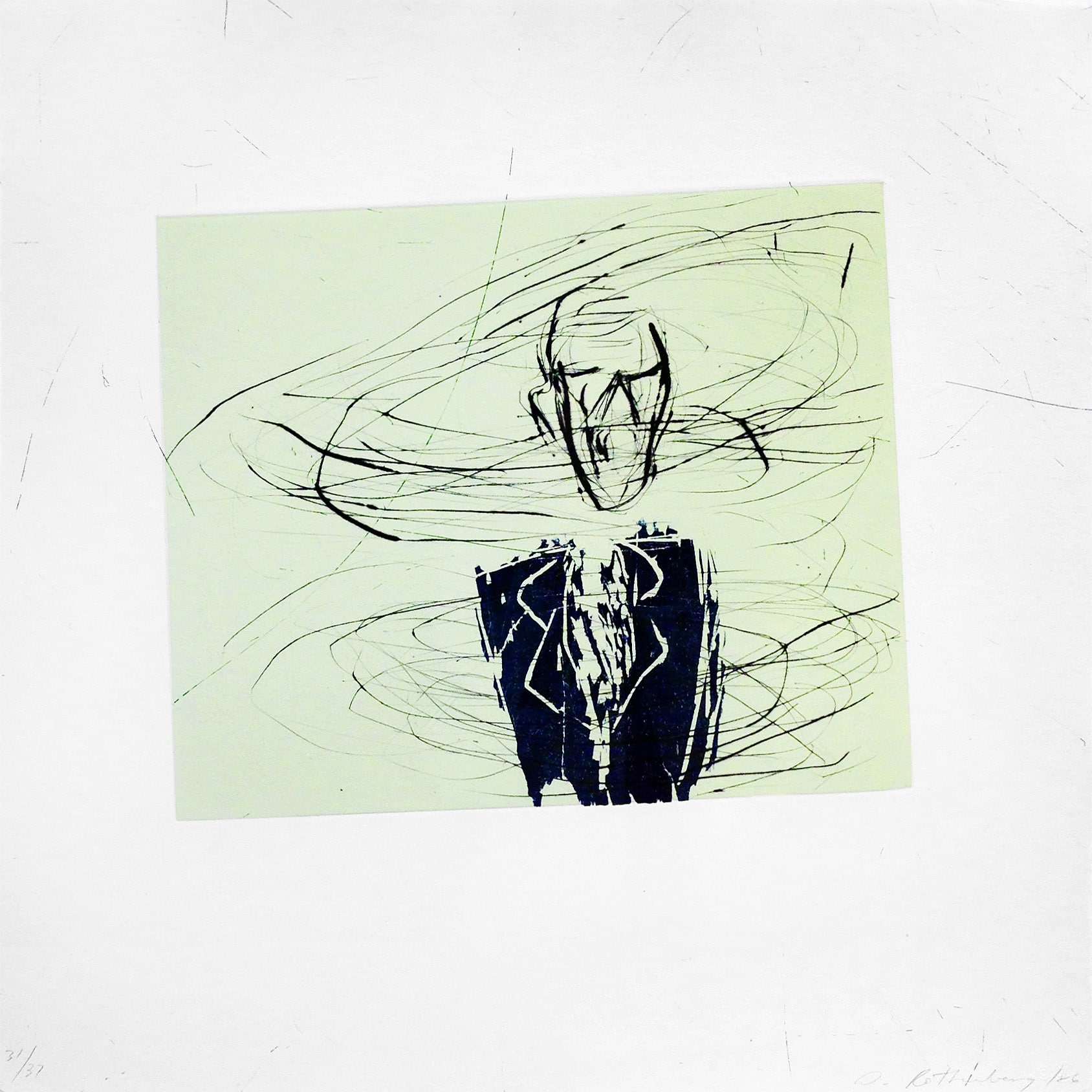

SUSAN ROTHENBERG

Susan Rothenberg

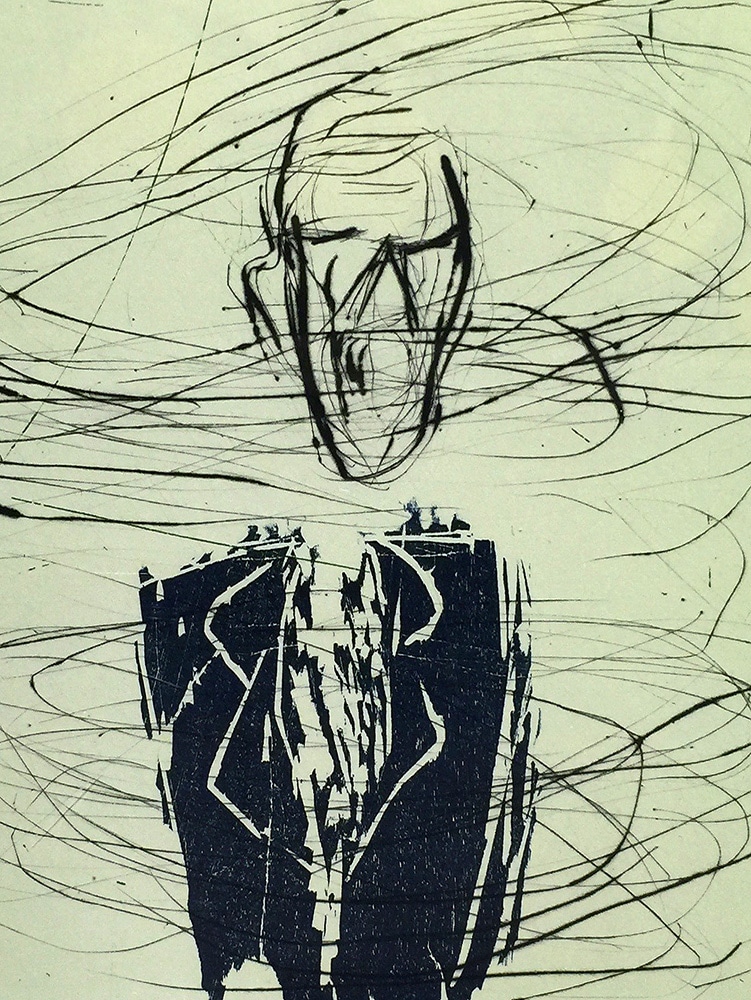

Breath-Man

1986

Four color drypoint, woodcut,

and engraving on paper

20-3/4″ x 20-1/4″ (52.7 x 51.4 cm)

Edition of 37

Susan Rothenberg (1945-2020) is an American artist known for her experimentation with the intermingling of figurative and abstract forms. From her early days as a painter and active member of the 60s and 70s New York art scene, Rothenberg has worked mainly with muted colors, black, and white. The artist paints or etches on flat, almost minimalist grounds, using the gestural expression of movement and recognizable figures and objects simultaneously as representations of specific people, events or types of movement and as forms through which to explore underlying emotional autobiography. In her own words, her paintings and etchings attempt to “catch a moment, the moment to exemplify an emotion,” showing things not “the way they are” but “exactly the way [they] can’t be.” Rothenberg currently lives and works in Galisteo, New Mexico, with her husband, artist Bruce Nauman.

Born in 1945 in Buffalo, New York to a grocery-store-chain executive and a casual watercolorist, Susan Rothenberg was a precocious child, and had an artistic urge and rebellious streak from an early age: sometimes, after being kicked out of class for talking out of turn, she would talk her way into an in-progress art class in a different part of her school. Outside of school, Rothenberg learned about art-making from a neighbor, a doctor and enthusiastic amateur artist whose interest in mixing collage, abstract and realistic painting seems to have stuck with Rothenberg throughout her career. Young Susan’s parents quickly noticed her passion and gave her art supplies, enrolled her in classes at an exceptional local museum, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and eventually paid for her to attend the Fine Arts School at Cornell University.

At Cornell, Rothenberg primarily studied sculpture. She found inspiration in the works of Lucas Samaras, and she made a series of alarm clocks with teeth, her style somewhere between the trippy eclecticism of Samaras and the uncanny materiality of the Surrealist object. But Rothenberg was as interested in dancing go-go—and ballet—as she was in learning sculpture. Dance, of course, is a medium particularly relevant to Rothenberg’s art: much in the way that dance takes place in the intersection of abstract music and essentially figurative, visually expressive physical performance, Rothenberg’s art is noted for its ability to incorporate figurative or quasi-figurative forms with the purely emotional color- and movement-based language of abstraction.

Also while she was at Cornell, Rothenberg befriended future Warhol superstar Mary Woronov, who would remain an important presence for the rest of Rothenberg’s artistic career. After, in the artist’s words, getting on her “high horse and decid[ing] to quit school,” Rothenberg spent a five-month hiatus on the Greek island of Hydra before following Woronov to New York City. It was in New York City that Rothenberg’s most significant artistic education began. There, she studied at a studio program that encouraged her to explore and learn from the local art scene.

Incidentally, in New York at that time, 1966-67, the art scene was undergoing one of the most pivotal moments in its history—arguably in all art history. Minimalism gave way to the diverse Post-Minimalist period, characterized by everything from the Happenings of Kaprow to the human-formal experimentation of Eva Hesse and of an evolving Robert Morris, with Johns’ and Warhol’s distinct schools of Pop Art folded into the mix, too. Rothenberg saw, absorbed, and participated in virtually all of these new movements, finding herself particularly drawn to the proto-performance art of Bruce Nauman and Joan Jonas. After sorting through all these influences, by the mid-1970s Rothenberg began her own full-fledged career, with her first solo show in New York in 1975 at the 112 Greene Street Gallery. In one of her most significant early works, First Horse (1974), a horse form, the same color and consistency as the surrounding ground, just barely emerges from abstract strokes of clay pigment. This piece marked Rothenberg’s transition from a purely abstract painter-sculptor to someone with a unique style that has marked her as one of the great new American artists who could not fit within traditional modernist categories. Her work was featured at the 1980 Venice Biennale in the American Pavilion, her presence making her one of the central figures in the “The Pluralist Decade” (the 1970s) of American art.

First Horse was the first of many: Rothenberg’s 1970s works often involved images of horses or parts of horses. But saying her artworks are ‘pictures of horses’ (or of ‘things’ at all) does not quite do them justice: they are just as much pictures of emotional states or of thought experiments. In the 1970s Rothenberg focused on how she could differentiate forms on the canvas without using the illusions of positive presence or negative space, using horses as a familiar jumping-off point for experimentation. Consequently her works tend to have a flat, matte sensibility, and many of her images can be read as both compositions of abstract shapes and representations of specific subjects.

In the 1980s, Rothenberg focused less on horses and more on human subjects, as well as characteristically expressive and sketchy depictions of boats and fantastic shapes. She participated in the major Zeitgeist show of Neo-Expressionist art at the Stedelijk, Berlin, but ultimately moved away from Neo-Expressionism because of its male-dominated tone. Trying to find her artistic home, Rothenberg experimented with a variety of media besides painting, including—as Breath-Man (1986) attests—drypoint etching. Like her mid/late-1980s paintings, her 1980s etchings are frenetic and energetic, yet carefully composed. Rothenberg uses wild lines to investigate the sense of speed and motion one can get from a still work of art. The dancing swipes that create the phenomenon of motion also have a purposeful ambiguity about them: is Breath-Man exhaling, or is he suffocating, or swimming? If this seems like an over-reading, consider that, “for Rothenberg, making…works on paper is a parallel activity to painting,” worthy of the same level of artistic attention—a belief that led her to avoid using any underdrawing or sketches for her horse paintings, for instance.

In 1989, Rothenberg married artist Bruce Nauman and moved with him to a New Mexico ranch. Since the move, Rothenberg has turned back to a more static style. She continues to combine figuration and abstraction by meshing forms within large, abstract grounds, and uses bold colors. She currently lives and works in New Mexico.